(Seriously, remember when NPH wasn’t Barney Stinson or Dr. Horrible or a major awards show host or anything other than Doogie Howser?)

Twelve years can make anyone’s memory spotty and mine is notorious for that, but I still think that my list encapsulates the movie as a whole. It’s commercial pop trash. It’s got some special-effects-driven battle scenes and it’s got some T&A, things that reliably sell tickets. The Nazi imagery I attribute to Paul Verhoeven’s particular (but not unique) lunacy and a maneuver I like to call “beating Godwin’s Law to the punch.” But let’s set the movie version aside for now.

Prior to seeing the movie (in fact, prior to this week) I had never read Starship Troopers. Which means I vaguely remember some people grumbling about the liberties taken with the Heinlein source material, but it didn’t mean much to me personally. Still, I think the existence of the movie helped raise the novel’s profile and I realized it was one of those sci-fi geek touchstones, which meant I felt like I should read it. Over a decade later, I can cross that off the list.

It’s funny thing how the various entertainment industries try to titillate us into consuming their offerings. With big-budget movies it’s sex and violence, boobs and explosions. With books it often seems to be the taboo allure of controversy, which therefore must be the highbrow intellectual version of sex and violence (assuming we’re going for a very oversimplified black-and-white contrast of books and movies. Which we are, what the hell, why not?). So sure enough, on the cover of the copy of Starship Troopers I borrowed from a friend, it is clearly marked as a “controversial classic!”

Having read the book it’s hard to see what all the fuss is about. There are good things and bad things about Starship Troopers purely from an entertainment perspective. It’s very readable, which is something not to be taken for granted when it comes to sci-fi. Heinlein wisely gave the book a first-person narrator who works his way up through the military from the level of raw infantry recruit, and then interspersed tons of details about everything from hierarchical organization to sci-fi tech used by the troopers. Heinlein himself had military experience and also a hell of an imagination for coming up with futuristic elements like powered armor, and he brings all of that to bear but always in the context of what it means to the average joe, as represented by the narrator Johnnie Rico. Johnnie is forever in learning mode, sometimes literally sitting in History and Moral Philosophy class, which means Heinlein can go off for pages at a time with naked political proselytizing, and he does, but he writes those scenes as competent dialogue (or maybe I’m just a sucker for the Socratic method). And let us not forget the Bugs. “Bug” is a sci-fi synonym for “freakishly inhuman alien” and “bug hunt” means “human soldiers fighting freakishly inhuman aliens in alien territory” and these terms are widely geek-known (even the movie Aliens references them) but – as far as I can tell – Heinlein originated them, so credit where credit is due. I read sci-fi (ahem, “speculative fiction”) for the ideas as much as anything, and Heinlein has those in spades. On the downside, the book has no subtlety and honestly very little plot – just when it seems that Johnnie is ready to go from passive audience-relating cipher to protagonist, the book ends. It’s also quaintly retro as far as the attitudes towards women (so co-ed shower scenes was definitely something Verhoeven came up with on his own) – but it was written in 1959, so it was probably downright progressive for having female pilots in the space navy at all, treating them like porcelain dolls or no.

So the controversy comes down to the politics, which is essentially extreme pro-militarism. One of the few things that survived the transition from the novel to the screen was the idea of a future society in which all civilians have rights protected by laws, but only citizens are allowed to vote (and presumably hold office) and only people with military service are considered citizens. If you have the time, energy and wrecking tools to diagram the grammatically-questionable sentence I just perpetrated, you might notice that the key word is “idea”. High-concept sci-fi often comes down to a single idea that the author finds interesting enough to explore at length. A war between humanity and an alien species wasn’t that innovative an idea even in 1959. But the idea of what the human side of that war might look like in the future, if then-current twentieth century governments collapsed and something new rose up, something based on military might and heroic sacrifice as ultimate virtues – that was something Heinlein found interesting enough to examine.

If you don’t find that interesting, Starship Troopers will bore you to tears. However, if you find that interesting but disagree with Heinlein’s conclusions – that force and the will to exercise it are the only things that guarantee prosperity; that only men who have proven willing to die for one another and the homeland can be trusted to do what’s best for society as a body politic – then good for you for having a brain and opinions of your own. Agree or viscerally disagree, though – it’s just a book. It’s an imaginary story about imaginary people in an imaginary world which happens to share some history with our own. Surely there are things more worthy of being deemed controversial. Actions can be controversial. Policies can be controversial. These things affect people’s lives. They matter. Even certain kinds of art can be controversial if their creation involves exploitation of some kind, because again, that’s a real person’s life affected. An idea in a novel is ephemeral. At most it can inspire other ideas, in support or rebuttal, which leads to discourse which is always a good thing. I guess you could argue that a radical idea in a book that no one speaks out against could find its way into the hands of an impressionable child and inspire the next History’s Greatest Monster, but … that possibility seems remote.

And, as always, there’s the question of authorial intent. Can an author examine an interesting idea without either explicitly skewering it or implicitly endorsing it? Does Heinlein’s vision of a Terran Federation with vaguely western NATO-ish ideals that is worth fighting an interstellar war to defend mean that he really wished in his heart of hearts that the Constitution would be abolished and a military-ruled meritocracy established? Is Starship Troopers a manifesto, or just an intellectual sandbox to play in? I did a little research and found that Heinlein really did try to do actual political organizing that was pro nuclear armament, to oppose the anti-nuke peaceniks, which sounds very Starship Troopers. On the other hand, I’ve read Stranger In a Strange Land, too, which is pretty hippy-dippy-trippy. Which one is the real Heinlein? Maybe both. Maybe, like Walt Whitman, he contradicts himself and contains multitudes. The point is it is never simple to interpret a work of literature, even one as unsubtle as Starship Troopers. For example, one of the things that jumped out at me about the book was the fact that Johnnie’s childhood friend Carl, the one who is more or less responsible for directionless young Johnnie joining the military in the first place, gets killed later in the book and merits nothing but a passing mention. I read that as a signal of how the military has been steadily dehumanizing Johnnie, and how that’s the ironic price a militaristic society has to pay: it may be a disciplined, orderly, prosperous society but its best and brightest are rational, self-sacrificing heartless killing machines. That’s what I got out of it, and to a large extent it doesn’t matter if that’s what Heinlein wanted me to get out of it or not.

I mentioned Godwin’s Law up above (on the off chance you’ve never heard of it: as an internet conversation/argument continues indefinitely, the chances of someone invoking Nazis approaches 100% certainty), and I recently ran across another interesting internet-meme: Poe’s Law. In brief, fundamentalism is impossible to parody because fundamentalism is already so exaggerated that any attempt to parody it simply looks like an accurate reflection. This creates two different phenomena: one is when a person sees an example of fundamentalism and says “this has GOT to be a joke”; the other is when someone creates a joke and a fundamentalist takes it very much to heart as a legitimate case of likemindedness. Which begs the question: is Heinlein’s Starship Troopers novel a straight passionate defense of kill-or-be-killed xenophobia as functional political doctrine, or a mockery of it?

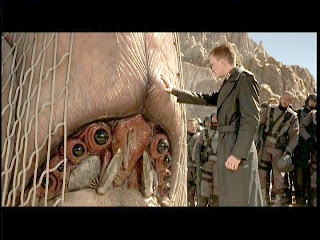

What about Verhoeven’s Starship Troopers film? A lot of people hated it because it seemed to basically glorify fascism. Which it does, but not in a way anyone could take seriously ... right? That picture way up above from the film, it comes from a scene near the end where the space infantry have finally captured a Brain Bug, a member of the Arachnid’s command caste, and Gestapo-NPH is mind-melding with it. He gets an emotional read on the Brain Bug and says “It’s afraid … it’s AFRAID!” and the space infantry goes nuts with victory cheers. I think this bears repeating: something called a BRAIN. BUG. Is found to be terrified of DOOGIE. HOWSER. And this symbolizes that the war is more or less won. This scene is FUCKING HILARIOUS. How could anyone think this was unironic?

Well, someone could. That’s the messy beauty of the human condition – interpretations vary. There’s an old saying about how it’s impossible to make an anti-war movie because war onscreen looks cool as hell. (Or words to that effect.) Some people are going to see Casper Van Diem kicking ass and getting laid and just think it’s all good in the hood. Some are going to laugh at him, not with him. And some are going to be appalled. And it’s probably worthwhile to bring all of that to the discourse, but again, I don’t think the future of civilization hinges on coming to consensus on middling 90’s sci-fi movies.

One last interesting (to me at least) piece of trivia on some of the hate for the Starship Troopers movie, which stems not from philosophical objections but the lament that the movie is not all that faithful to the book. And man do geeks hate it when you’re unfaithful to the source. Apparently, if you think Verhoeven set out to film Starship Troopers and butchered it, you’re operating from a faulty premise. Verhoeven just wanted to make a slick sci-fi bug hunt movie, and someone at the studio realized that it had a superficial similarity to Starship Troopers. While the movie was already in production, the rights to the novel were acquired by the studio. And then semi-compatible parts of it were incorporated from there on out and the title was changed. Frankly, if that apocryphal bit of Wikipedia lore is true, I’m amazed the two works bear as much resemblance to one another as they do.

No comments:

Post a Comment